UNITED IN ANGER: A HISTORY OF ACT UP STUDY GUIDE

UNIT 5: DISCUSSION GUIDE

Discussion Section 1: Gran Fury: Posters and Graphics

In her introduction to This Will Have Been: Art, Love and Politics in the 1980s, art curator Helen Molesworth identifies ACT UP artists as important contributors not merely to the history of social protest in America but to the shifting art scene of the 1980s:

In New York the artists and cultural practitioners involved in ACT UP brought all their theoretical and aesthetic acumen to bear on the group’s activities, changing the look and feel of street protest as a result. Through a network of anonymous collectives, artists populated ACT UP demonstrations with a strong graphic sensibility that produced snappy posters and phrases self-consciously appropriated from corporate advertising strategies. (30)

Gran Fury was one such collective within ACT UP, producing agit-prop (explicitly political art) around issues in the AIDS crisis. Take some time examining Gran Fury’s most notable graphics.

Clip #1

2. What other visual materials widely found in culture do Gran Fury’s posters remind you of?

3. Gran Fury’s posters, billboards, and installations had multiple functions. What various kinds of cultural work did they do?

Clip #2

4. A dynamic tension often exists within explicitly political art. How do you see the aesthetic and the activist elements of Gran Fury interacting?

Discussion Section 2: Video Activism: Testing the Limits and DIVA-TV

Founded in 1987, Testing the Limits was a filmmaking collective of artists and AIDS activists. Testing the Limits worked primarily in the documentary format, interspersing interviews with AIDS activists with “guerilla footage” of AIDS demonstrations, often set to music and edited to reflect the then-popular sensibilities of music videos.

DIVA TV was founded in 1989 as a video-documenting affinity group within ACT UP. Its goal was to challenge the lack of informed coverage of the AIDS epidemic in the mainstream media and renew a sense of urgency about AIDS through video activism. Believing that “[i]t is the cultural medium of our society which fosters the spread of HIV/AIDS,” DIVA TV appropriated the medium for their own purposes, both by producing and broadcasting their own work and by providing footage to mainstream media venues. In January 1993 a weekly AIDS Community Television cable program debuted, created by James Wentzy and reviving the name of DIVA TV. “ACT UP Live!”, a weekly call-in show on Manhattan public access cable television, was launched in January 1994.

1. What recognizable elements or tropes of the video medium did Testing the Limits draw on in its documentaries, including Testing the Limits and Voices from the Front? Where have you seen those video tropes before, and how are they used differently by Testing the Limits?

Clip #3

2. What does DIVA-TV stand for?

3. What various styles or genres of television broadcast did DIVA TV experiment with?

Clip #4

Clip #5

4. TV allows for access to large markets, but it is also marked by the constraints of advertiser dependency that controls a great deal of the content. As a result, commercial TV audiences have been groomed to be ideal consumers of products and sound bites of information. How did DIVA-TV create activism that could be mass consumed by viewers? How did the medium help to create the message?

Clip #6

Clip #7

5. ACT UP existed before the Internet. There was no email. Information had to be shared by “phone trees”, mailings, and posters wheat-pasted on the street. Today, social media is an organic part of daily life. It is both broader and narrower than conventional media. It allows individuals to be heard, but only by a select and closed group. In a way it could give the illusion of being heard by your own community while mainstream media remains unaffected. How might today’s social media reshape activist messages about AIDS? How did the lack of internet communication help ACT UP to organize?

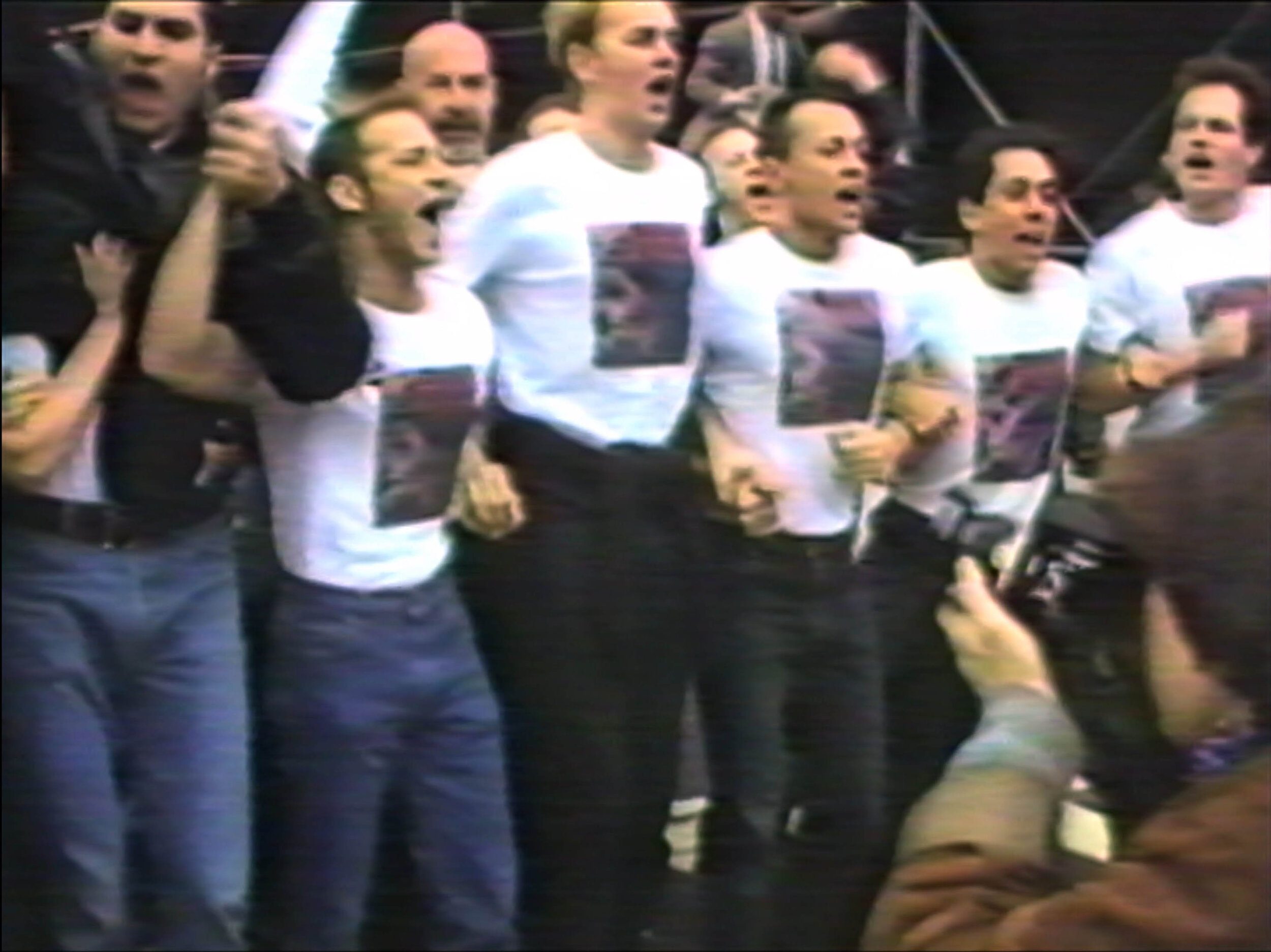

Discussion Section 3: Performance Art, Performance Protest

ACT UP art activism emerged against a vibrant backdrop of artistic expression in New York City in the 1980s. Performance art provided an especially apt politico-aesthetic response for ACT UP, as it integrated the immediacy of the art form and its historical resistance to commodification (and thus containment) with ACT UP’s need for powerful public demonstrations of rage and grief.

Performance art is defined by Professor Jules Odendahl-James as “artwork conceived with the artist’s/performer’s body as central canvas, frequently in concert with other representational mediums (film, dance, sculpture, painting, photography), which invites active spectatorial engagement/interaction; a predominately visual mode of ‘story telling’ that embraces durational, sensorial and frequently a-narrative modes of that telling, pushing the physical extremes for both audience and artist. In that the artist’s body is canvas, this work is frequently rooted in questions of identity, identification, aesthetics, value, and the politics of representation. It challenges notions of coherence as essential to meaning and boundaries of ‘taste’ and aesthetics that dominate the mainstream art world.”

1. In addition to the political funerals discussed in Unit 3, what examples of performance art as protest do you recall seeing in United in Anger?

Clip #8

Clip #9

Clip #10

Clip #11

2. How would you describe the aesthetic of these protests? In other words, what is artful or innovative about them? How does their meaning depend at least in part on their aesthetic quality?

3. How are bodies used as the central canvas in ACT UP performance art?

4. What are the effects of ACT UP’s performance art protests? What did they make you think and feel?

5. Make the argument that art has political utility.

STUDY GUIDE HOME

UNIT 1: HISTORICIZING ACT UP

UNIT 1: PROJECTS AND EXERCISES

UNIT 2: THE STRUCTURE OF ACT UP

UNIT 2: PROJECTS AND EXERCISES

UNIT 3: ACT UP IN THE STREETS

UNIT 3: PROJECTS AND EXERCISES

UNIT 4: THE POLITICS OF HIV/AIDS MEDICINE

UNIT 4: PROJECTS AND EXERCISES

UNIT 5: ACTIVIST ART

UNIT 5: PROJECTS AND EXERCISES